A’Lelia Walker: The Joy Goddess of Harlem’s 1920s

A'Lelia Walker was a socialite and style icon in Harlem during the Roaring Twenties. The only daughter of businesswoman and hair care industry pioneer Madam C.J. Walker, she carved out her own legacy as a financier of Black artists and a philanthropist. Her life, filled with opulent gatherings and a who's who of the African American cultural vanguard, earned her comparisons to a real-life Jay Gatsby, except her story was not a work of fiction, and her wealth was self-made, inherited from one of America’s great Black entrepreneurs.

As a patron of the arts, A'Lelia helped define the post-World War I social scene above 110th Street through her glamorous, extravagant parties. She was an heiress with beautifully appointed homes and a penchant for hosting music-filled soirées. Whether entertaining guests at Villa Lewaro, her inherited grand estate in Irvington, or at her pied-à-terre in Harlem, her gatherings were legendary.

These vibrant salons brought together a brilliant mix of Harlem Renaissance contributors such as Langston Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston, Paul Robeson, Florence Mills, James Weldon Johnson, Countee Cullen, Carl Van Vechten, and Dr. W.E.B. Du Bois, alongside European aristocrats, African royalty, and other cultural, social, and intellectual luminaries of the Jazz Age.

Langston Hughes, poet laureate of the New Negro Movement, never used the phrase himself, but in popular culture A'Lelia has since been crowned “the Joy Goddess of Harlem’s 1920s,” inspired by his vivid portrayal of her in his 1940 autobiography The Big Sea. Per Hughes:

"It was a period when, at almost every Harlem upper-crust dance or party, one would be introduced to various distinguished white celebrities there as guests. It was a period when almost any Harlem Negro of any social importance at all would be likely to say casually: 'As I was remarking the other day to Heywood—,' meaning Heywood Broun. Or: 'As I said to George—,' referring to George Gershwin.

It was a period when local and visiting royalty were not at all uncommon in Harlem. And when the parties of A'Lelia Walker, the Negro heiress, were filled with guests whose names would turn any Nordic social climber green with envy.

It was a period when every season there was at least one hit play on Broadway acted by a Negro cast. And when books by Negro authors were being published with much greater frequency and much more publicity than ever before or since in history. It was a period when white writers wrote about Negroes more successfully (commercially speaking) than Negroes did about themselves. It was the period (God help us!) when Ethel Barrymore appeared in blackface in Scarlet Sister Mary! It was the period when the Negro was in vogue."

A’Lelia Walker, heiress and patron of the arts. Carl Van Vechten, 1927.

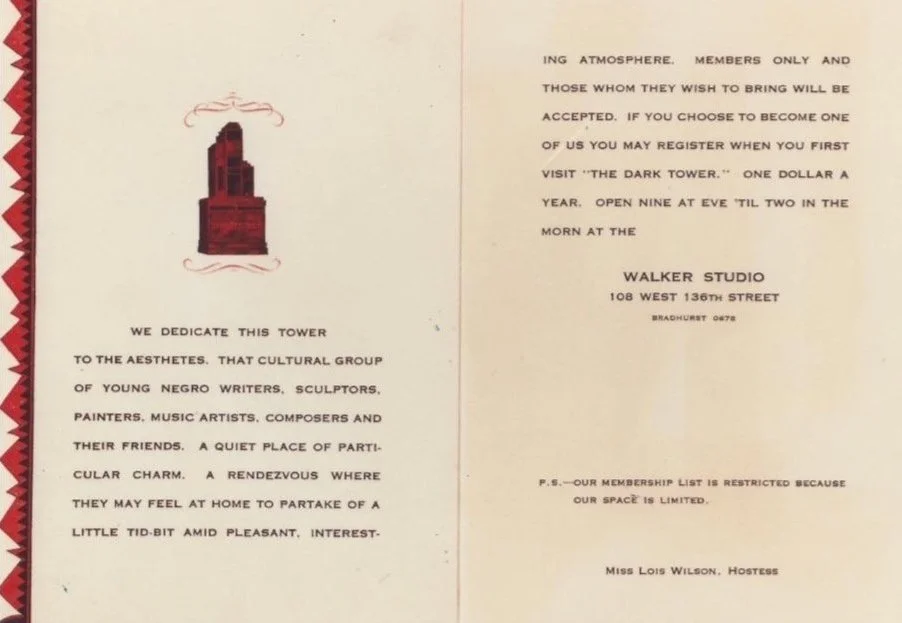

Invitation to The Dark Tower, A’Lelia Walker’s Harlem salon. Circa 1920s.

Invitation to The Dark Tower salon. Circa 1920s.

A’Lelia Walker’s car with chauffeur in front of her inherited Harlem townhouse. 1915.

The Dark Tower salon. James Van Der Zee, 1929.

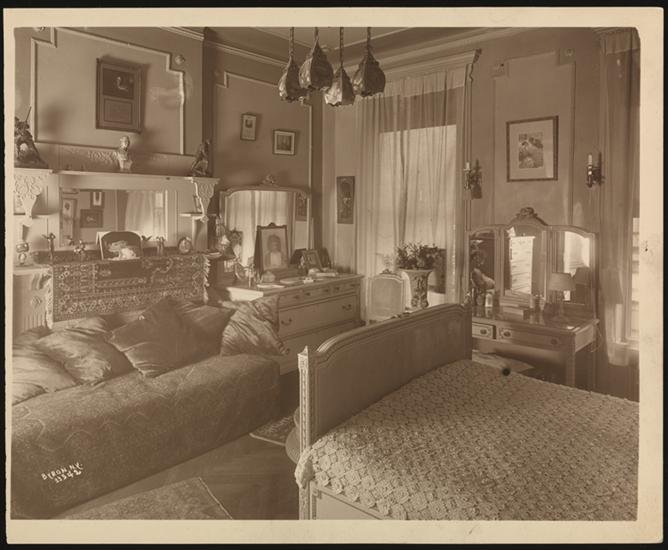

A’Lelia Walker’s bedroom in her Harlem townhouse. 1915.

A’Lelia Walker. 1926.

A'Lelia Walker getting a manicure. George Rinhart, 1920.

A'Lelia Walker at her inherited estate, Villa Lewaro. Circa 1930s.

A’Lelia Walker hosted her daughter Mae’s wedding reception at her estate, Villa Lewaro. The event was recognized by The New York Times. 1923.